BHI FaxSheet: Information and Updates on Current Issues

Poor Revenue Estimates Costs States Jobs and Investments

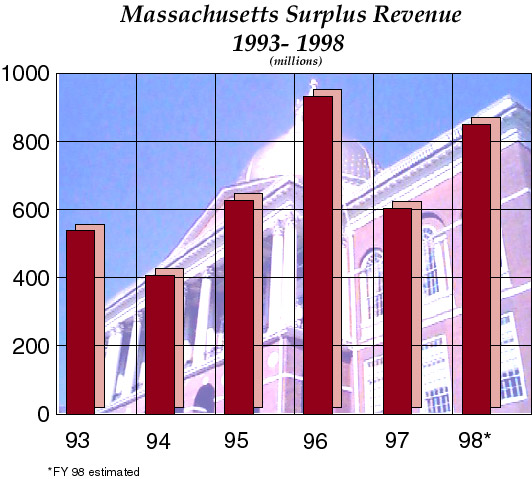

A new economic analysis reveals that poor revenue estimates combined with the ongoing economic expansion have created a new phenomenon – a year-in-and-year-out pattern of large surplus state revenues. One New England state, Massachusetts, has accumulated almost $4 billion in these surplus revenues over the last six years, about 4% of budgeted spending. The continued collection of surplus revenue imposes a drag on state economies. The Beacon Hill Institute analysis found that, last year alone, this fiscal drag cost Massachusetts almost 73,000 jobs, more than $2.5 billion in payrolls and almost $11 billion in capital equipment (factory space and machines, computers, delivery trucks and so forth) that would otherwise have been in place.

Surplus revenue is money that the state collects in excess of its budgeted spending for a given fiscal year. Because, for Massachusetts, surplus revenues have become steady and large, they have taken on the character of a "stealth" budget, a hidden revenue source from which to fund predictable but unbudgeted state spending needs.

The phenomenon of surplus revenues is not limited to Massachusetts. According to one report, surplus revenues are currently running about $34.5 billion, about 8.5% of total state spending, for the 50 states. [1] Another report puts the current-year figure for five New England states (excluding Vermont) at close to $1.5 billion. [2]

The fiscal year 1999 Massachusetts budget is expected to be about $19.5 billion. But, if current economic conditions continue and there is no tax cut, the state will end up collecting FY 99 surplus revenue of $773.4 million. Taking this surplus revenue into account, actual FY 99 revenue will run closer to $20.3 billion, about 4% more than what the state is saying now that it plans to collect and spend. If the state enacts a tax cut in calendar year 1998, the actual surplus for FY 99 will be smaller.

Government uses surplus revenues by making supplemental appropriations or by saving them. Supplemental appropriations are for new state spending or refunds to taxpayers. Saving goes to various funds, including the stabilization or "rainy day" fund. Line 1 of Table 1 shows the surplus revenues ("stealth budget") for the period FY 93-99. Lines 2 shows the portion spent as supplemental appropriations and Line 3 shows the portion saved. The major portion, about 70%, has gone into spending and the rest into saving. Only a small portion of the accumulated surplus revenues – $235 million in FY 97-98 – was refunded to taxpayers. The rest went for new spending or saving.

Table 1 - Massachusetts Stealth Budget, FY 93-99 ($ millions)

93 94 95 96 97 98* 93-98* 99** (1) Surplus Revenue ("Stealth Budget") 537.2 406.9 626.9 930.9 603.9 848.6 3,954.4 773.4 (2) Supplemental Appropriations 524.4 380.1 490.0 484.5 382.9 514.0 2,775.9 530.7 (3) Saved 12.8 26.8 136.9 446.4 221.0 334.6 1,178.5 242.7 *FY 98 data are estimates based on currently available data.

**Projection based on FY 93-98 and assuming no CY 1998 tax cut.

When a Surplus Revenue Becomes a Stealth Revenue

At the beginning of the fiscal year, the executive branch declares, in its annual budget, how much it plans to spend and how much it plans to collect in revenue over the next twelve months. Because no entity, public or private can anticipate exactly how much it will spend and how much it will collect in revenue, the budget is a statement of planned spending and of planned revenue collections.

Actual, as opposed to planned spending and revenue collections will vary with economic conditions and with other conditions beyond the control of government. A snowy winter will force government to spend more than planned on plowing the roads. A fast-growing economy will cause it to collect more than planned in revenues and to spend less than planned on welfare.

In some years, therefore, the state will experience a revenue shortfall and in other years a revenue surplus. Revenue surpluses acquire a stealth-like character, however, when they turn into supplemental appropriations for routine expenditures that were not included in the beginning-of-fiscal-year budget or when they are “saved” mainly to avoid making refunds to taxpayers.

An indication that government is engaging is stealth budgeting is its intentionally or unintentionally omitting routine and predictable spending plans from its budget or repeatedly underestimating revenue flows. Revenues belatedly declared as “needed” for some emergency or contingency are depicted as “windfalls” to be used responsibly rather than as refunds to taxpayers.

Spinning the Stealth Budget

Stealth budgeting is an outgrowth of a tradition – long considered respectable, even high minded – of underestimating government revenues and then using the surplus revenues to pay for supplemental spending measures or additions to rainy-day funds and the like. As a matter of principle, state revenue forecasters and taxpayer watchdog groups offer “conservative” revenue estimates in order to hedge against possible revenue shortfalls and then, when their estimates prove to be underestimates, argue for using the money for some emergency or for some responsible purpose.

In FY 97, Massachusetts included in its supplemental appropriations $10 million for “maintenance to state colleges and universities,” $30 million for “implementation and oversight of educational technology projects” and $13 million for “repairs and improvements to rinks, pools and other properties.” Such appropriations appear not to represent emergencies, but rather routine expenditures that should have been factored into the FY 97 budget when it was originally conceived.

There are calls to set aside some of the FY 98 surplus revenues for expenses associated with the Central Artery Project or “Big Dig.” There are also frequent warnings of the need to set aside funds now for “less rosy” days ahead.

Massachusetts budgeted $583 million in state appropriations for the Office of the Secretary of the Executive Office of Transportation and Construction for FY 98. Now there are proposals to set aside some of the FY 98 surplus revenue for the Big Dig. But the EOTC bears responsibility for managing the Big Dig. Arguably, in drawing up the FY 98 budget, the Legislature should have considered the long-predicted spending needs of the Big Dig in tandem with those of the EOTC.

The Economic Consequences of Stealth Budgets

Surplus revenues exert unwanted effects on economic activity. This is because the higher tax rates that are needed to maintain excess revenue flows exert negative effects on the willingness of business to create jobs and to create capital in the form of machinery, computers, factory space and the like.

The alternative to collecting surplus revenues is cutting tax rates by enough to bring actual revenues into line with planned spending. Just as higher tax rates negative effects, lower tax rates exert positive effects on the economy.

Suppose, for example, that Massachusetts had cut tax rates for calendar year 1997 by enough to eliminate that year's surplus revenue. [3] Our analysis shows that it could have brought about this result by cutting the tax rate on earned income from 5.95% to 5.2%. The result would have been the creation of more than 72,000 jobs, over $2.55 billion in payroll and more than $10 billion in new capital. See Table 2.

Table 2 - Effects of Cutting the Earned Income Tax Rate from 5.95% to 5.2%, CY 1997 [4]

$2.55 billion 72,982 $10.84 billion -$818 million $127 million -$691 million The lower tax rate would have caused a “static” revenue loss of $818 million, which would have been offset in part by a “dynamic” gain of $127 million, made possible by the expansion in the state payroll. The net result would have been a loss of $691 million in tax revenue, approximately the amount of revenue the state would have lost in calendar year 1997 by eliminating the stealth budget.

Conclusion

Massachusetts has been collecting revenues that exceed budgeted spending by about 4%. The surplus revenue thus collected amounts to a stealth budget – money not reported by the state at budget time but that will predictably become available during the fiscal year to fund routine spending and saving requirements.

The most effective and economically beneficial antidote to stealth budgets is a reduction in tax rates, which simultaneously deprives government of the surplus revenue and offers a stimulus to the economy. Because it took the accumulation of almost $4 billion in surplus revenues to bring about this action, however, it is well to consider a more effective antidote. One answer is a law that requires the state to pay back, with interest, revenues that exceed budget by more than, say, 1%. The Legislature could be permitted to use surplus revenues exceeding this amount for emergency purposes on a vote of 2/3 or more of its members.

Appendix A. The Massachusetts budgetary process

The budgetary process begins early in the prior fiscal year. For example, a budget for fiscal year 1999 begins in January 1998 with the Governor's proposal known as House 1. Once it is submitted, House 1 is reviewed by the House of Representatives where all appropriation bills begin.

The House Ways and Means Committee considers the Governor's budget recommendation (House 5500 for FY 99) and, with revisions, proposes a budget to the full House of Representatives, which sends it to the Senate. Thereafter, the budget is considered by the Senate Ways and Means Committee, which in turn proposes a budget to be considered by the full Senate. After Senate action, a legislative conference committee made up of six members appointed by the House and Senate leadership crafts a compromise budget for further consideration. After it is voted upon by both houses, the budget is sent to the Governor.

Under the Massachusetts Constitution, the Governor may veto the budget in whole or disapprove or reduce specific line items. As a check on the Governor, the Legislature may override the Governor's veto or specific line-item vetoes by a two-thirds vote of both the House and Senate. At the end of this process, when the Governor has signed a budget, the legislation is officially called the General Appropriation Act.

State law requires the Legislature and the Governor approve a balanced budget for each fiscal year. Any time during the fiscal year, the Legislator or the Governor may propose further spending known as Supplemental Appropriation Acts. The Legislature can legally increase the state's budget as long as it does not cause the budget to be unbalanced.

Once the fiscal year is finished, the Legislature can still appropriate additional monies. The Supplemental Appropriation Acts allow the Legislature to spend additional monies without taxpayers' knowledge. In essence, this allows the Legislature to use the Acts as a mechanism to prevent surpluses from being returned to taxpayers.

Appendix B. Methodology

We use data from a table found in bond prospectuses issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts called the Budgeted Operating Funds Operations – Statutory Basis. Total revenues come from the line titled "Budgeted Revenues and Other Sources." Total expenditures come from the line titled "Budgeted Expenditures and Other Uses." Total expenditures as reported by the Comptroller's office include expenditures from the General Appropriations Act, all supplemental spending attributed to each fiscal year, prior year appropriations continued (PACs) and reversions. [5]

To derive the "Original Signed Budget," we subtract all supplemental appropriations from Total Expenditures and Uses. (See Table 3 below) This represents the amount that the Legislature approved and the Governor signed, including PACs. Next we derive "Surplus/Deficits" for each FY by subtracting "Original budget Signed" from "Total Revenue and Other Sources." We subtract supplemental appropriations because they were not part of the original General Appropriation Act. "Reported Surplus/Deficit" is the surplus or deficit reported by the Comptroller's office. This amount is calculated by subtracting "Total Expenditures and Uses" from "Total Revenue and Other Sources."

Table 3 - Massachusetts State Budget

FY 93

FY 94 FY 95 FY 96 FY 97 FY 97 Beginning Fund Balances

Reserved or Designated

236.2

110.4 79.3 128.1 263.4 225.1 Tax Reduction Fund

0

0 0 0 231.7 91.8 Stabilization Fund

230.4

309.5 382.9 425.4 543.3 799.3 Undesignated

82.8

142.6 127.1 172.5 134 277.8 Fund Balance Restatement

0

0 0 0 0.7 (128.0) Total

549.4

562.5 589.3 726.0 1,173.1 1,266.0

Revenues and Other Sources

Taxes

9,929.9

10,606.7 11,163.4 12,049.2 12,864.5 13,700.0 Federal Reimbursement

2,674.1

2,901.2 2,969.7 3,039.1 3,019.6 3,375.0 Departmental and other revenue

1,327.1

1,187.9 1,273.1 1,208.1 1,267.9 1,285.0 Interfund Transfers and Other Sources

778.5

853.9 981.0 1,031.1 1,018.0 948.6 Total Revenue and Other Sources

14,709.6

15,549.7 16,387.2 17,327.5 18,170.0 19,308.6

Expenditures and Uses

Programs and Services 12,683.6

13,416.2 14,010.3 14,650.7 15,218.8 16,504.0 Debt Service 1,139.5

1,149.4 1,230.9 1,183.6 1,275.5 1,243.2 Pensions 868.6

908.9 968.8 1,004.6 1,069.2 1,069.6 Interfund Transfers to Non-budgeted Funds and Other Uses 5.1

48.4 40.4 42.2 385.5 112.9 Total Expenditures and Uses 14,696.8

15,522.9 16,250.4 16,881.1 17,949.0 18,460.0 Supplemental Appropriations

During FY 412.6

242.3 442.4 93.2 136.8 0 During FY 35.4

18.0 1.5 2.8 2.4 0 Subsequent to FY 76.4

119.9 46.1 388.5 223.4 0 Subsequent to FY 0

0 0 1.8 20.3 0 Total Appropriations 524.4

380.1 490.0 486.3 382.9 514.0 Original Budget Signed 14,172.4

15,142.8 15,760.4 16,394.9 17,566.1 18,460.0

Ending Fund Balances

Reserved or Designated 110.4

79.3 128.1 263.4 225.1 96.2 Tax Reduction Fund 0

0 0 231.7 91.8 3.5 Stabilization Fund 309.5

382.9 425.4 543.3 799.3 866.1 Undesignated 142.6

127.1 172.5 134.0 277.8 249.6 Total 562.5

589.3 726.0 1,172.4 1,394.0 1,215.4

Surplus Revenue 537.2

406.9 626.9 930.9 603.9 848.6

Saved 12.8

26.8 136.9 446.4 221.0 334.6

Note: Using a 5.15% tax rate I got a net tax revenue effect of -$738 million, a little over the -$726 million surplus for calendar year 1997. The economic effect are a little, but not much larger.

Important Note: This tax cut is, in addition to the temporary increase in personal exemptions for 1997, and the marginal tax rate could have been cut by even more if these exemptions had not been increased.

Footnotes

[1] State Government News, April 1998, p. 12.

[2] USA Today, May 27, 1998, p. 8A.

[3] This is figured on a calendar year, rather than a fiscal year basis. CY 1997 surplus revenue (obtained by averaging the FY 97 and FY 98 surpluses) was about $691 million, or the amount of revenue the state would have lost in CY 97 by cutting the tax rate on earned income to 5.2%.

[4] This tax cut is in addition to the temporary increase in personal exceptions for 1997, and the marginal tax rate could have been cut by even more if these exemptions had not been increased.

[5] Reversions are unspent monies that are returned to the general fund.

Posted 7/8/98: Revised on 7/11/07 14:07