BHI FaxSheet: Information and Updates on Current Issues

Capital Gains Hike Would Hurt Low-Income Taxpayers Most, Cost Millions in Capital Spending and Local Revenues

June 1999

In 1994, the Massachusetts legislature passed a cut in the tax on long-term capital gains (assets held a year or more). [1] The rate, then 6%, was lowered to 5% for assets held 1-2 years, 4% for 2-3 years, 3% for 3-4 years, 2% for 4-5 years and 1% for 5-6 years. The rate was to go to zero for assets held six or more years.

The Fiscal Year 2000 budgets approved by the Massachusetts House and Senate would rescind the planned reduction in tax rates on assets held five years or more. This would, in effect, raise rates on these assets, creating a minimum 2% tax on capital gains. [2] See Table 1.

Table 1: Current and Proposed Taxes on Long-Term Capital Gains

| Years Held | Current Tax Rates | Proposed Tax Rates | |

| At Least | But Less Than |

(%) |

(%) |

|

1 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

|

3 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

|

5 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

|

6 |

0 |

2 |

|

The House and Senate proposals would require Massachusetts investors to pay an additional $131.2 million in capital gains taxes in 2002. The additional revenue amounts to about .6% of the budget.

Highest Tax to Fall on Lowest Income Group

There is a perception that government should raise the capital gains tax because it falls almost entirely on the rich. That perception is, however, wrong. Taxpayers at all ends of the income spectrum realize capital gains and pay capital gains taxes. Moreover, the increase in the capital gains tax rate brought about by the House and Senate budget proposals would fall far more heavily on capital gains filers in the lowest income group than it would on capital gains filers in the highest income group.

Here are the facts: Of the 684,268 Massachusetts taxpayers who reported capital gains or losses in 1997 (the latest year for which data are available), 46% were taxpayers with an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $50,000 or less. Only 24% had an AGI of $100,000 or more. Notably, the largest fraction (21%) fell in the lowest income group (under $20,000) and the smallest fraction (8%) fell in the highest income group ($200,000 or more). [3] See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Fraction of Massachusetts Capital Gains Filers by AGI Group, 1997

Source: U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 1999. See footnote 3 for details.

Insofar as low-income filers reporting capital gains or losses realize high capital gains relative to their taxable income, a rise in the capital gains tax will impose a relatively heavy economic burden on those taxpayers. It turns out that the House and Senate budgets impose just such a burden.

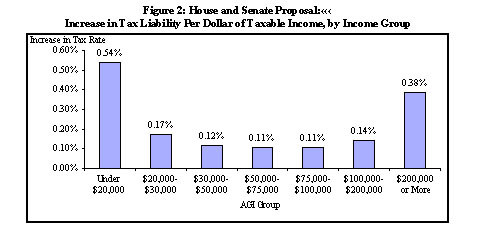

The new law would raise the average tax rate on capital gains by .52 percentage point by 2000 and by 1.08 percentage point by 2001. By applying this tax increase to state taxpayers reporting capital gains or losses, it is possible to determine, by income group, the increase in the tax rate that these taxpayers would bear under the new law. Figure 2 shows the increase in tax for each income group.

As shown, the lowest income group would suffer the highest tax hike. Taxpayers reporting capital gains with an AGI less than $20,000 would pay .54% more of their taxable income in taxes, whereas taxpayers reporting capital gains with an AGI of $200,000 or more would pay only .38% more. [4] Put differently, the tax increase would be 42% greater for the low-income taxpayers than it would be for the high-income taxpayers.

While this result might seem counter intuitive, it is easily explained. Low-income households often sell assets in order to support themselves over periods of economic hardship (unemployment, for example). If a household sees its income fall, say, from $40,000 per year to $20,000 per year, it is not

Source: U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 1999. See footnote 3 for details.

likely to reduce its consumption by half. Rather, it is likely to finance part of its consumption out of capital gains, on which it will be compelled to pay taxes. Raising the capital gains tax imposes a greater burden on this household than it would on a wealthier household that might realize capital gains in the course of everyday market trading.

Among Massachusetts taxpayers who would be affected by the tax hike, there are many more in the lowest AGI group than there are in the highest AGI group. Of Massachusetts taxpayers who reported taxable income and whose AGI was less than $20,000, 142,985 reported capital gains or losses. The figure for taxpayers with an AGI of $200,000 or more was 52,569. There were therefore almost three times as many low-income as high-income taxpayers reporting capital gains or losses. The capital gains hike is far larger for low-income than for high-income taxpayers and falls on far more low-income than high-income taxpayers.

Economic Effects on Massachusetts

As mentioned, the House and Senate proposal would raise the effective capital gains tax by 1.08 percentage point. This would exert adverse economic effects on the state economy. Because Massachusetts is a high cost-of-living state, a rise in the capital gains tax – or any tax – deters people from working and investing in the state. That, in turn, deters business from spending on new capital – factories, computers, office buildings, warehouse space and other equipment and structures. The further result is a shrinkage in tax revenue from other sources, including the revenue collected by local governments on commercial property.

As a result, by 2002, there would be $920.9 million less in capital construction than there would have been under the current rate schedule. Local governments would collect $8.92 million less in tax revenue. See Table 2.

Table 2: Effects of Rescinding Current Capital Gains Law

|

Effect

on Average |

Effect

on State Tax |

Effect

on |

Effect

on Local Property |

|

|

2000 |

+ 0.52 |

+ 31.6 |

- 446.6 |

- 4.33 |

|

2001 |

+ 1.08 |

+ 97.2 |

- 923.0 |

- 8.95 |

|

2002 |

+ 1.08 |

+ 131.2 |

- 920.9 |

- 8.92 |

* Fiscal year (all other changes are shown by tax year).

**Differences between the 2001 and the 2002 numbers stems from a projected decrease in the relative importance of capital gains in 2002 as a fraction of unearned income.

The proposed rise in the capital gains tax would therefore fall with particular severity on low-income taxpayers and would impose substantial losses on the economy. It would also create a climate of uncertainty about the after-tax return that investors can expect to realize on their assets. The addition to state revenues that would be realized appears not to justify the cost, measured in terms of both equity and economics, that it would impose.

The Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization that performs economic analysis on public policy issues of importance to Massachusetts voters and taxpayers. The estimates provided here were obtained by using BHI's State Tax Analysis Modeling Program (STAMP). Details on the application of STAMP to this BHI FaxSheet and further methodological details are available on request.

Footnotes

[1] In December 1994, in conjunction with a legislative pay raise package, Governor William F. Weld signed a bill cutting the state's capital gains tax rate (see State House News Service, Roundup-December 15, 1994).

[2] Given that this change would (by Massachusetts Department of Revenue estimates) affect 56% of all assets, it would cause a substantial rise in the effective tax rate on capital gains (computed by weighting the rate applicable to each holding period by the fraction of assets held over that period). This, in turn, would have a large and negative impact on Massachusetts capital spending and on tax revenues collected by local governments.

[3] U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin, Spring 1999, “Total File, All States, Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 1997.” See http://www.irs.ustreas.gov/prod/tax_stats/soi/ind_agi.html, 97IN54CM.EXE. We used data on federal individual income tax returns for Massachusetts taxpayers.

[4] Ibid. The methodology underlying these estimates is as follows: Let CG be the ratio of total capital gains to the number of filers reporting capital gains or losses in a given income group. Let TI be the ratio of total taxable income to the number of all filers in that income group. Then the tax rate rises by (.0108*CG/TI)*100 percentage point. This assumes that average taxable income is the same for taxpayers reporting capital gains as it is for all taxpayers in a given income group.

Comments: fconte@beaconhill.org.

HTML revised on 11-Jul-2007 1:42 PM

©Beacon Hill Institute, 1996-2005. All rights reserved.